Looking back at a union that works for those who serve NSW.

For 125 years, the Public Service Association of NSW has been looking out for the people who look after the state.

The union has seen its members fight in two world wars, endure countless economic ups and downs and brawls with state governments.

The PSA has also evolved with the ever- changing workforce that performs the role of delivering services for the people of NSW.

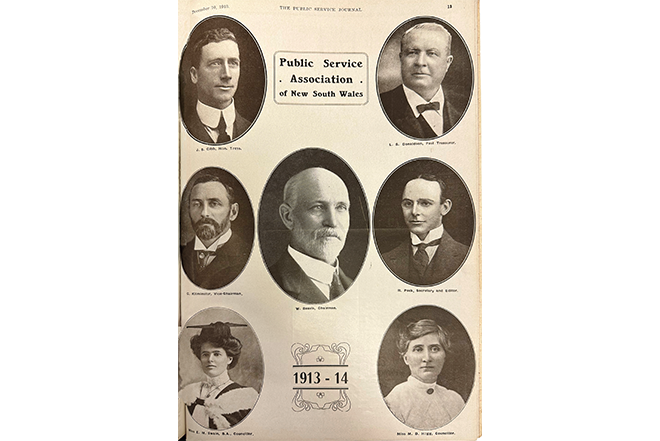

When the PSA formed 125 years ago, it was a male-dominated group of clerical workers in ties. Today, the union is made up of more than 65 per cent women.

Its ranks of clerical members are bolstered by thousands of other essential workers: Prison and Youth Justice Officers, Schools staff, National Parks Rangers and Police Special Constables. Its members are in government offices, prisons, schools, universities, group homes and TAFE colleges.

They work in national parks, courthouses, state forests and on rivers and dams.

For 125 years, the machinery of the state government has been powered by PSA members. They are the people delivering policy that affects the health, education and movement of millions of people in NSW.

These members are joined by CPSU NSW members, working in areas such as disability support, higher and vocational education, disability support, power generation and our water resources.

PSA CPSU NSW members are on hand throughout citizens’ entire lives, helping them through school, TAFE and university, issuing their driver’s licences, marriage certificates and being by their side in the justice system. PSA members in Births Deaths and Marriages are there to document the beginning of people’s lives and the end.

When first established in 1899, the Public Service Association of NSW was reluctant to call itself a union. Instead, it fashioned itself a body set up to promote the interests of Public Sector workers throughout the then colony of NSW.

The first edition of the organisation’s precursor to Red Tape, The Public Service Journal, however, set the groundwork for “the means for combined action in matters affecting any section of the Service”.

The Public Sector had, in the preceding decade, bore the brunt of job losses during the depression of the 1890s. Members of the new association were keen not to repeat the experience, knowing industrial action may be required to preserve their jobs and conditions and prevent the State Government of the day from taking out its economic woes on its workers.

However, when an industrial arbitration system was established in 1908, the PSA was denied a role in the new set-up.

However, this did not stop the PSA launching its first major campaign covering equal pay, superannuation and conditions two years later. Eventually, in 1919 the PSA was registered under the Trade Union Act 1881.

In 1919, mass rallies of members gave the PSA access to the arbitration court that decided other industrial relations matters. Sadly, new legislation

in 1922 again excluded the PSA from the arbitration system. However, the union later forced the Lang Labor Government to amend the legislation to accommodate the PSA.

When the world economy again entered depression, this time in the 1930s, massive Public Sector job cuts were averted. However, the PSA was forced to negotiate over a sector-wide pay cut and the Treasury raided superannuation to make up for revenue shortfalls.

With a chair at the table, the PSA began to create links with other unions, including those representing blue-collar workers.

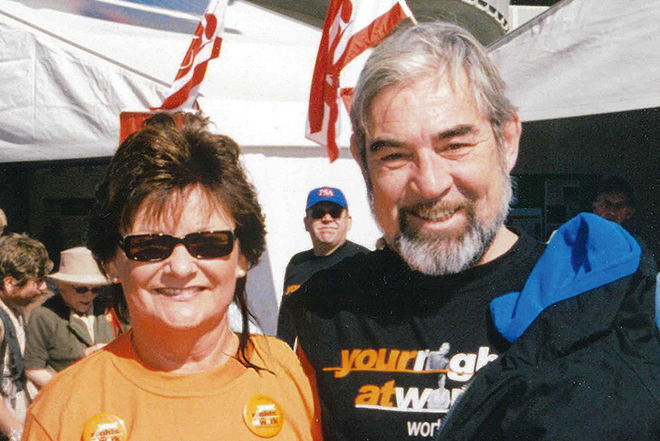

“During these times, members saw the importance of fighting for their wages and conditions,” said current PSA CPSU NSW General Secretary Stewart Little. “Today we continue these battles, walking alongside other unions in demanding a better deal for workers in NSW and Australia.”

The Depression also focused the PSA’s attention on the plight of the women in its ranks.

While the pages of the early PSA publications were filled largely with male faces, there were sections dedicated to the organisation’s small female membership, with articles centred around Boer War widows, fashion, fundraising and the expense of living in Sydney.

Women had filled the ranks of the Public Sector during the First World War and, even when servicemen returned, remained a vital part of the Government’s workforce.

But old habits die hard and women were still too often marginalised in the workplace, including within the union. Early networking by the PSA was done at events such as ‘smoking concerts’, where members would light up in venues such as Sydney Town Hall and talk shop, with female members denied entry to the main area and sidelined to a nearby gallery.

However, more women continued to enter the Public Sector, mainly in clerical roles, in the early 20th century and by 1929 a quarter of the NSW public service was female.

However, since the Harvester Case of 1907 that set minimum wages – and a lower wage for women – this section of the PSA membership was legally discriminated against with every pay packet.

The Depression-era pay cut and the treatment of women members saw the PSA take action.

In 1932, thousands attended meetings in Sydney Town Hall and King’s Hall in Hunter Street to demand any cuts to wages be rescinded.

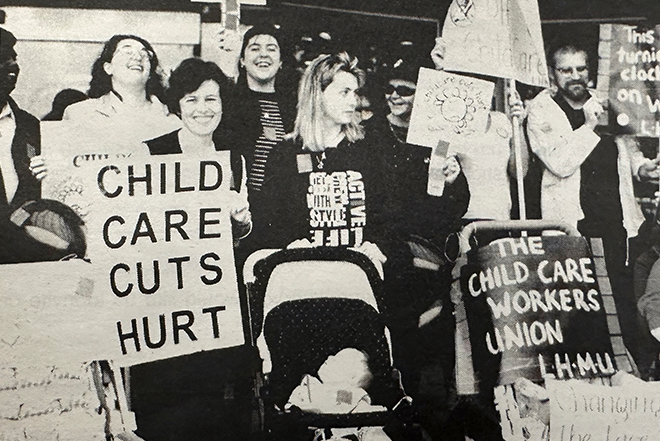

The PSA also pushed for the then- revolutionary idea that women and men be paid equally.

The cuts to wages had particularly hit women in the Public Sector hard, while some male workers worried they would be overlooked in favour of cheaper, female employees.

Therefore, the PSA launched a campaign to restore wages to levels before the Depression cuts, with an increased focus on women and lower- paid roles.

The PSA joined 52 other organisations to form the Council of Action for Equal Pay. The PSA Women’s Auxiliary, which dated back to the early days of the union, strongly promoted the issue, with substantial support from then President, George Weir.

As the country moved towards the Second World War, demands for equal pay increased, as once again more women entered the workplace to fill vacancies created as workers were sent to conflict in Europe, North Africa and the Pacific theatres.

These demands became a constant theme for campaigns throughout the union’s 125 years in action. Equal pay cases were won in Transport, during the famous Librarians’ case in 2002 and again in 2019, when it was found staff in schools had been discriminated against due to the sector’s gender mix.

“The schools decision came after a lot of hard work and was a great win for our members,” said Mr Little. “It was a perfect example of how systematic discrimination undervalued women performing vital work in our education system.

“Some members received pay increases of 36 per cent.

“The long-running, constant battle for equal pay proves how important unions are. We need constant vigilance to hold our employers to task.

“Governments don’t grant pay increases out of a sense of largesse. Workers need unions fighting on their behalf.”

While always looking to protect members’ wages and conditions, strike action was rare for the PSA. The first time its members walked off the job was in 1976, when Corrective Services staff took action.

It wasn’t until 17 November 1980, that the PSA, which had just moved into its present Clarence Street premises, went on a membership-wide general strike.

In that action, up to 80 per cent of members walked off the job, paralysing the state. The strike was in reaction to the new Public Service Act, which, in an all- too-familiar move, was regrading current positions and using outside appointments to undermine wages and conditions.

The strike, which unsurprisingly earned the ire of the Murdoch press, saw 5000 workers attend a stop work meeting and thousands marched on Parliament House to demand the Act be rescinded.

Just as with pay equity, the PSA was a trailblazer in the world of post- retirement savings. In the 1980s, the PSA made robust demands for a better superannuation system, a full decade before it was enshrined in federal law.

“Not only was superannuation good for our members, it reduced their reliance on pensions upon their retirement,” said Mr Little. “It is just one of the many initiatives from the Australian union movement that has not only helped members, but it has also helped wider society, too.”

In 1985 and 1986, the PSA launched a series of strikes, campaigns and even a sit-in at the Education Department to win permanency for School Administrative and Support Staff, who were overwhelmingly employed in casual and part-time roles.

One of the School Administrative and Support Staff members involved in the action, Sue Walsh, went on to become the longest-serving President of the union.

In 2023, the PSA won commitments from both major parties dealing up to the state election to end the state’s over-reliance on insecure roles in the school system.

When Labor Leader Chris Minns won the poll, he kept to his promise and gave secure roles to more than 8000 support staff in schools: some of whom had languished in insecure positions for more than decade.

To mark the union’s 100th birthday, Labor Premier Bob Carr addressed celebrations as the PSA prepared for the challenges of the 21st century, and for the PSA’s 120th anniversary, the union led the 2019 May Day march through the streets of Sydney.

Industrial action continues to be an important tool in your union’s arsenal. In 2017, members defied a court order and headed into the centre of Sydney on Valentine’s Day, braving driving rain to demand the government not outsource disability services.

In 2022, a statewide strike demanded an end to a wages cap that had artificially held salaries down, even as post-COVID inflation bit. The wages cut was seen by the membership as particularly insulting given the enormous role played by the Public Sector in keeping the state operating as COVID-19 shut down entire swathes of the economy.

“Our union doesn’t just work at the negotiating table: we are out on the streets for our members, too.

“We filled Macquarie Street in Sydney and had rallies throughout regional NSW,” said Mr Little. ”We even had members set up rallies in some smaller centres such as Tweed Heads and Broken Hill.

“When the Liberal National Party Government fell the following year, it was in no small part due to rallies such as that one and our relentless campaigning against the unfair wages cap and the out- of-control privatisation agenda under the not-so-awesome foursome of O’Farrell, Baird, Berejikian and Perrottet.

“We presented the parties with a number of demands; an end to the wage cap, the return of an independent Industrial Relations Commission, the abolition of the Government Sector Employment Act and a stop to relentless privatisation. These were all achieved or are in the pipeline.

“In 125 years, we have evolved from an association representing people who work for the government to a union that can campaign and change the government.”

The PSA CPSU NSW is no longer a club largely made up of white men, and now better reflects the state its members serve. In 2017, the union established

its Aboriginal Council, a vehicle that was one of the first of its kind in the Australian industrial relations landscape. The Council was set up to improve the working lives of First Nations members.

“Traditionally the union movement and the Aboriginal community have always been heavily involved with each other,” said current Chair of the Aboriginal Council, Darrell Brown. “Aboriginal people have always been employed in the lower-skilled workforce and suffered a lot of discrimination in gaining employment.

“The union movement has supported us since the 1860s. Given this history of always being in the trenches together, it’s only appropriate that there be an Aboriginal Council to advise the PSA on all things important to our community. We provide cultural expertise to the PSA to better the employment and living conditions for Aboriginal community.

“The PSA takes great pride in being one of the first unions to enshrine an Aboriginal Council in its constitution.”

In 2023, the Pride Council was established for the LGBTQI+ community, meeting regularly with MPs and making submissions on issues such as anti- discriminatory legislation.

“Our union has changed as NSW has changed,” said Mr Little. “We are a diverse group of members serving Australia’s most diverse state. The pioneers of the union in 1899 would not recognise the PSA of today.

“But I imagine they would be rightly proud of the work we have done to protect the wages and conditions of our members who do so much for NSW.

“There is power in a union and we are proud to wield this power for a better state for all.”

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *